By Alejandro Gómez

For those who have been fighting the HIV/AIDS pandemic for decades, the arrival of antiretroviral treatment in 1996 changed everything. Before the development of an effective treatment for HIV/AIDS, the focus was on decreasing the number of new HIV infections and reducing the pain of those who were already diagnosed with AIDS. Patients typically lived only about three more years after their diagnosis. However, since 1996, people living with HIV who have access to antiretroviral treatment can expect to live long, healthy lives, with a life expectancy comparable to that of the general population.

Just like other major technological and biomedical advances, antiretroviral treatment for HIV was only accessible to a relatively small group of people in rich countries for the first few years after it entered the market. Due to a combination of structural racism, economic injustice, and greed from pharmaceutical companies, treatment remained largely inaccessible in the developing world, including sub-Saharan Africa, where most of the new HIV infections were being reported.

A new hope appeared in 2003, when U.S. President George W. Bush introduced the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, PEPFAR for short, a program that put billions of dollars toward the fight against HIV/AIDS in developing countries. The results of the program have been astonishing. It is estimated that since PEPFAR made antiretroviral treatment more easily accessible, the world has prevented 25 million AIDS-related deaths.

PEPFAR continues to be a central piece in the global response to HIV/AIDS. The most recent Global AIDS Update from UNAIDS estimates that 58% of all international financial assistance for HIV in 2022—or around US$ 4.8 billion—came from PEPFAR. Most of this money was used to cover the costs of antiretroviral treatment for individuals living with HIV in over 50 countries.

Despite being considered one of the most successful aid programs in American history, the future of PEPFAR is in danger—and so are the lives of the millions of people living with HIV who depend on it. Last month, Republicans in the U.S. Congress refused to move forward with the five-year reauthorization of PEPFAR, which for the last 20 years had enjoyed bipartisan support. The reason for this gridlock comes down to the debate surrounding sexual and reproductive health and rights in the United States. Republicans are anxious that PEPFAR is funding nonprofit organizations that, in addition to providing life-saving HIV care, also give access to abortion-related services. This is not entirely false, some of the organizations funded by the program do support abortion in their countries. However, since the creation of PEPFAR, U.S. policy ensures that taxpayer money is not used to fund abortions. Organizations supported by PEPFAR that provide abortion-related services need to look for alternative sources of funding for those programs.

The deadline for the reauthorization of PEPFAR passed on September 30th. Representatives from the U.S. government have ensured that, in the short-term, PEPFAR will continue to fund HIV services in participating countries. However, the decision to not reauthorize the program puts into question its long-term sustainability and exposes how vulnerable aid programs are to domestic politics. There is also a cruel irony to this case: the same Republican party that in 2003 made history by creating PEPFAR and saved millions of lives is now the main opponent of the program, justifying its stand with a “pro-life” argument.

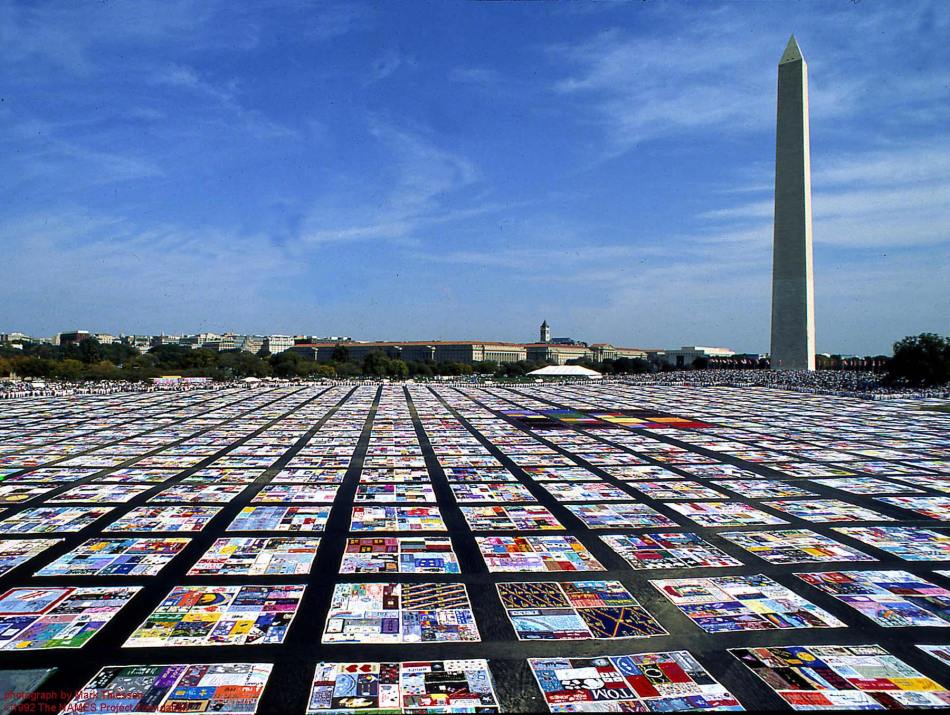

It is hard to believe that a decision can be “pro-life” when it disregards the lives of millions of people living with HIV. The global response to HIV/AIDS cannot be sustained without PEPFAR, at least not in the current funding landscape. A sudden drop in the international funding for HIV could erase decades of progress in the fight against the virus, and it could even take some parts of the world back to a pre-1996 period, when a positive HIV diagnosis meant a death sentence and people were dying in the hundreds of thousands. The real “pro-life” stand in this matter is to save PEPFAR.

The threat to PEPFAR is also warning the world of what needs to be done in the long-term to ensure the sustainability of the global HIV/AIDS response. First, national governments need to diversify their sources of funding and invest more in their HIV programs. A sustainable HIV response requires local ownership and commitment, and relying almost exclusively on money from PEPFAR leaves communities vulnerable to political changes and budgetary constraints. Second, global health actors need to keep HIV/AIDS as a priority on the development agenda. With the decrease of AIDS-related deaths throughout the last two decades, it is tempting to classify HIV/AIDS as a problem of the past. However, now more than ever funding is needed to keep the 39 million people living with HIV on treatment and continue researching a potential vaccine and cure. The fight is not over until the world has zero new HIV infections and zero AIDS-related deaths.

Photo Credits: US Department of State via Openverse

0 comments on “Pro-life, but Not for Those Living with HIV: The Case of PEPFAR and the U.S. Congress”